DeLilloan

"Underworld" is more urban pastiche than cohesive novel, but damn it radiates.

Hello, dear readers.

Real quick, what I’ve read since we last hung out: Martyr! by Kaveh Akbar (really enjoyed the surprising places it goes); McTeague by Frank Norris (holy shit, hold on to your teeth, might write an issue on it later); and Demon Copperhead by Barbara Kingsolver (picaresque, recommend to everyone).

Oh, and I finally read Underworld, the 827-page Big American Novel that had been sitting on my shelf for years, my fifth Don DeLillo book.

This is Issue 27. I wrote it at the home of the Hollywood Pirtheads.

The first DeLillo novel I read was White Noise, his 1985 National Book Award winner and most famous work. I was in college. I did not enjoy it.

It felt to me like he kept beating us over the head with his point: consumerism, commercialism, death. The incessant lists of products and brands grated, like, yeah, we get it. But I had also read the (in)famous 2001 B.R. Myers essay “A Reader’s Manifesto,” with its incisive send-up of White Noise, before reading White Noise, and that surely colored my experience.

This key part from Myers rang true to me as I read White Noise, but would I have felt that way without having been told to beforehand?:

“This is the sort of writing, full of brand names and wardrobe inventories, that critics like to praise as an "edgy" take on the insanity of modern American life. It's hard to see what is so edgy about describing suburbia as a wasteland of stupefied shoppers, which is something left-leaning social critics have been doing since the 1950s… DeLillo's characters talk and act like the aliens in 3rd Rock From the Sun, which would be fine if we weren't supposed to accept them as dead-on satires of the way we live now. The American supermarket is presented as a haven of womblike contentment, a place where people go to satisfy deep emotional needs.”

I tried DeLillo again when he published his first (and only) short story collection, The Angel Esmerelda, in 2011. Here was a chance to dip back into this Great American Novelist’s vibe in bite-sized helpings. I loved the stories. They felt brutalist and unflinching, especially “Baader-Meinhof,” which ran in the New Yorker in 2002. Now I had improved to a 50/50 track record on enjoying DeLillo.

Next I read End Zone (1972) and adored it: high school football as nuclear war. It was the convergence of 1970s American anxiety, omnipresent violence, and teenage apathy, all with a coating of West Texas dust over it. More “North Dallas Forty” (the gritty 1979 Nick Nolte movie) than Friday Night Lights.

Then I read The Silence, DeLillo’s slim 128-page 2020 novella imagining a mysterious national power outage. I thought it was cartoonishly bad and simplistic—the characters mostly just rattle off lists of vaguely ominous things as they sit around wondering what’s going on—and yet the book kind of stayed with me, part of a recent streak of vague-disaster-not-fully-explained novels. (The Silence has multiple mentions of crypto, by the way.)

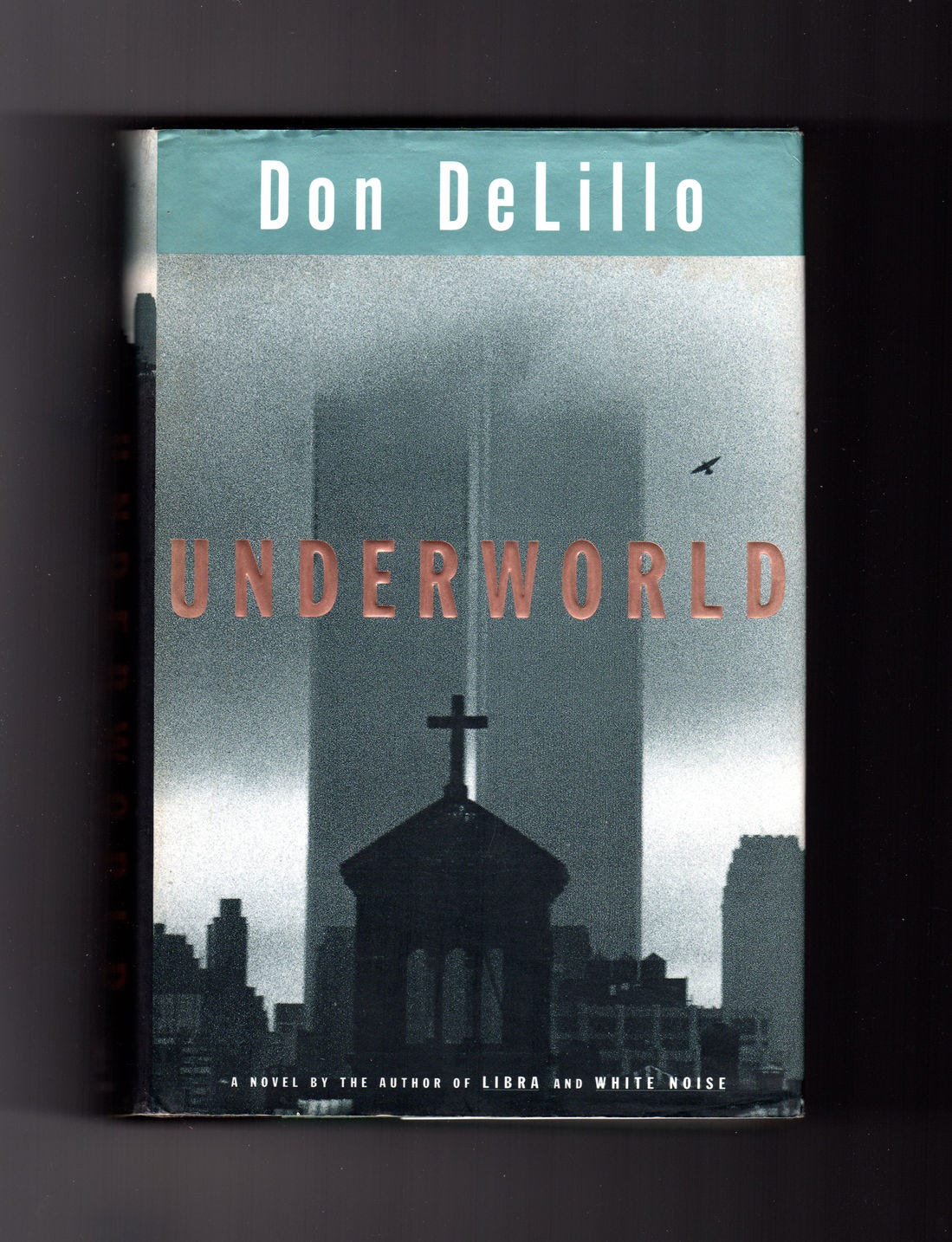

And finally, last month, I pulled Underworld from our home shelves. It was one of a handful of Big Books I’ve long owned but hadn’t gotten to yet. (And yes, the original cover depicted the Twin Towers, shrouded in fog, just four years before any image of those buildings would take on a different meaning forever.)

There is a vague byzantine skeleton of a plot in Underworld: the backstories of the many people who come into possession of the home run baseball Bobby Thomson slammed to give the New York Giants the NL pennant over the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1951. Indeed, the opening 96 pages of Underworld, originally published as “Pafko at the Wall” in Harper’s in 1992, are an incredible, indelible panorama of characters real and fictional dropped into a real-life moment of sports history.

I also appreciated the intricate structure of the novel, in which everything is told in reverse, finally ending in the reveal of the night when teenaged Nick Shay accidentally shot a man.

But Underworld as a whole is more pastiche of New York images than cohesive plotted novel. Its scenes and set pieces serve to illustrate DeLillo’s pet themes, the things usually called “DeLilloan”: nuclear warfare; waste and trash; collective national anxiety; urban systems; sports as a metaphor for society; the specter and inevitability of death. But in Underworld, they rang far less didactic for me than in White Noise.

In my 2018 piece about End Zone at The Paris Review, I wrote that the character Gary Harkness becomes “fascinated by words and phrases like thermal hurricane, overkill, circular error probability, post-attack environment, stark deterrence, dose-rate contours, kill-ratio, spasm war. At this point, we are squarely in Don DeLillo territory: the language is meant to exhaust, to glaze eyes. The melding of Gary’s football routine with his inner nuclear preoccupation is a macro effect.”

But your eyes never glaze in Underworld.

The simplest and best way I can convey my lasting impressions of Underworld is to share some of the passages I underlined with delight.

Here’s Nick Shay describing how obsessive he and his wife Marian become about garbage collection and disposal after he starts working in waste management: “Marian and I saw products as garbage even when they sat gleaming on store shelves, yet unbought. We didn't say, What kind of casserole will that make? We said, What kind of garbage will that make? Safe, clean, neat, easily disposed of?”

Marian trying to convince Brian Glassic, her husband’s coworker with whom she’s having an affair, to smoke heroin with her—absolutely brutal: “I want to get you in deeper. Take a chase. I want to get you in so deep you’ll stop eating and sleeping. You’ll lie in bed thinking about us. Doing our things in a borrowed room. You’ll be able to think about nothing else. That’s my program for you, Brian.”

This comparison of how people behaved when news broke of the JFK assassination made me think of my generation’s closest equivalent shared experience, 9/11: “When JFK was shot, people went inside. We watched TV in dark rooms and talked on the phone with friends and relatives. We were all separate and alone. But when Thomson hit the homer, people rushed outside. People wanted to be together. Maybe it was the last time people spontaneously went out of their houses for something. Some wonder, some amazement. Like a footnote to the end of the war.”

After Nick Shay, now 57, catches up with the artist Klara Sax, now 72, in the Nevada desert, decades after the affair they had when he was a teenager—this rings so true to me of the experience of reconnecting briefly with someone you haven’t seen in years: “Seventeen. That’s how old I was last time I saw her. Yes, that long ago, and after all this time it might seem to her that I was some invasive thing, a figure from an anxious dream come walking and talking across a wilderness to find her […] I could lift the younger woman right out of the chair, separate her from the person in the dark plaid pants and old suede blazer who sat talking and smoking […] We’d said what we were going to say and exchanged all the looks and remembered the dead and missing and now it was time for me to become a functioning adult again.”

This description of the preparation and first few minutes of any house party: “First there was an empty room. Then someone appeared and began to put things on a table, to move the magazines and picture books and put out bowls and crocks and cut flowers and then to reinstate some of the picture books but only the ones that claimed a status of a certain sumptuous kind. Then a few people arrived and there was sporadic conversation, a little awkward at times, because not everyone knew everyone. Then the room slowly filled and the talk came more easily and the faces shed some layers.”

And finally, as a MetroNorth commuter myself, this stuck with me more than any other passage in the book—it’s about an utterly minor character, but that’s beside the point, and Underworld’s genius is in conveying so many vivid New York moments using its entire cast of characters, major and minor:

“Charlie walked through the semiswank lobby, done in Babylonian art deco, and nipped around the corner to his Swedish masseuse, who karate’d his aching lumbar for ten minutes. Then he wheeled into Brooks Brothers and picked up a couple of tennis shirts because what’s more fun than an impulse buy? He double-timed it across Madison to the Men’s Bar at the Biltmore, where he massively inhaled a Cutty on the rocks and was out the door in half a shake and skating across the vast main level of Grand Central, the Bobby Thomson baseball jammed into the pocket of his topcoat—a Burberry all-weather that he loved like a brother and that went especially well with the suit he was wearing, a slate gray whipcord made for Charlie by a guy who did lapels for organized crime—because he’d decided the ball was no longer safe in his office and he wanted his son to have it, for better or worse, love or money, real or fake, but please Chuckie do not abuse my trust, I could fall down dead passing the stuffed mushrooms at dinner and this is the one thing I want you to take and keep and care for, and he went striding through the gate just in time to make his train, which was the evolutionary climax of the whole human endeavor, and he bucketed up to the bar car, filled with people who more or less resembled Charlie, give or take a few years and a few gray hairs and the details of their evilest dreams. The last express to Westport.”

There is some sense of pride and achievement in finishing a Big Book. Underworld was one of a handful on our shelves that I’ve checked off in the past year, along with Bleak House and Magic Mountain. But an ability to finish off a Big Book doesn’t mean you can get through every Big Book, or should even try. I’m unashamed to share I could not get through JR by William Gaddis. I’ve tried twice. (I’m suspicious of people who claim it’s one of their favorite books—is it, really?) And while I adored Ulysses, I could not get through Finnegan’s Wake, and don’t expect to try again in this lifetime. People have told me they can’t get through Infinite Jest. (I’ve read it, but I tell people it’s not DFW’s best work anyway, and I mean it; read his nonfiction essays or his short stories or The Pale King instead.)

It’s okay to give up on a Big Book slog. (I recently wrote about the merits of quitting.) But if you’re up for it, Underworld is worth the investment of time and mental patience, whether you’ve read DeLillo before or not.