Hiro Protagonist

Neal Stephenson's "Snow Crash" is an all-time classic and coined the term "metaverse." Does it still feel relevant today? Does that matter?

Welcome back to Writing About Reading! Now with new and improved custom domain. (Ooooh, aaaah.)

If you only read this newsletter/blog/content receptacle in your email inbox, you wouldn’t have noticed, but you can now find us (me) at www.writingaboutreading.com.

One other housekeeping note: Substack Notes is a new feature that lets Substack writers share quick updates without sending out a whole issue. I can use it to send you a little snack, if you will, about what I’m reading and what I recommend. In fact, I posted one last week.

To get my Notes, visit the Substack web site (you’ll see my Notes in the Notes tab) or download the (free) mobile app (you’ll get a notification when I post a Note). The feature also allows you to easily reply to my Notes, and I hope you will.

This is usually where I share what I’m reading right now. This week, it’s Sensation Machines by my friend Adam Wilson. In the past few weeks, I finished: Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow by Gabrielle Zevin (as good as advertised); Under the Dome by Stephen King (audiobook performed by Broadway’s Raul Esparza!); Stella Maris by Cormac McCarthy (do read The Passenger, but skip this unnecessary, dull companion); and Big Swiss by Jen Beagin (most fun novel I’ve read this year, highly recommend).

And now, for Issue 16, we’re going into the metaverse.

In February, I reread Snow Crash, Neal Stephenson’s seminal 1992 sci-fi novel that is credited with coining the word “metaverse.” I reread it as homework of sorts before getting the chance to interview Stephenson on the Decrypt podcast in March.

I first read it in middle school, circa 2002, age 15, when a boyfriend of my older sister gave me his copy. It felt like being passed down something cool and illicit, and the reading experience felt like a revelation.

On reread, at age 35, I was struck by how much Stephenson got right, and also how much he got wrong.

In Snow Crash, the hero/protagonist, named Hiro Protagonist (pretty great), works as a delivery boy for the pizza mafia, but spends his free time in the metaverse as a mercenary hacker/stringer gathering information and gossip for pay.

In Stephenson’s 1992 imagining, the metaverse is an open cyber realm where anyone can choose whatever avatar they wish, though most people are lazy and just rent a Clint or Brandy, two default male or female avatars (a touch that is both funny and logical, as is common in Stephenson’s stuff). Hiro, who is half Black, half Korean, wears a black kimono and totes two samurai swords.

The first two chapters of Snow Crash are a thrill ride. Hiro is rushing to deliver a pizza on time, lest he incur the wrath of the feared Uncle Enzo, and needs the help of Y.T., a minivan-harpooning teen girl on a skateboard, after Hiro crashes into a backyard pool. (Stephenson also introduces the term “burbclave” here, and those are a very real thing today.) Great world-building. But the byzantine plot spins out from there, bringing in ancient Sumerian language and multiple shadowy agencies, and the story kind of lost me this time around.

But I’m more interested in thinking about Stephenson’s metaverse, and other visions of the metaverse in science fiction, than in reviewing Snow Crash as a reading experience. I’ll just say that if you consider yourself a sci-fi devotee and haven’t read Snow Crash, you should.

What Stephenson got right: Hiro is believable to me. In our era, he’d be a TaskRabbit tasker or Uber Eats delivery guy. And the metaverse of Snow Crash is believable, because a digital realm, where you can explore and meet other avatars, exists today, and we even call it by the same name. No one can ever take that proof of influence away from Stephenson, even if Mark Zuckerberg is trying his best to co-opt the concept. (William Gibson should also get credit for the “cyberspace” of Neuromancer (1984) which obviously influenced Stephenson.)

Of course, people debate what “metaverse” actually means today. Is there one open metaverse, or multiple distinct metaverses? When you log on to an internet-connected game, are you in the metaverse, or the closed universe of that game? In crypto, there are game realms that explicitly call themselves a “decentralized metaverse” (Decentraland; and The Sandbox, where Snoop Dogg bought virtual land). In non-crypto gaming, there have been games for years that look to me like they could reasonably be called metaverses (Half Life; The Sims; Animal Crossing: New Horizons, which came at the perfect time at the start of the pandemic and built a virtual society so intricate that the Bank of Nook cut interest rates to spur spending).

On the Decrypt podcast, I asked Stephenson straight up: What do people get wrong when they talk about the metaverse? He said it’s when they “talk about a metaverse, or multiple metaverses… that's always a signal to me that somebody doesn't get it." So in the view of the author who coined the term, there's one metaverse, like the one internet. Sounds nice, but I don’t think we’re there yet, unless you define the entire social web as the metaverse. (My developing take is that any platform or app on which you’re represented by a digital persona—Twitter, Discord, Reddit—is basically akin to the metaverse.)

The other common assumption people get wrong, Stephenson said, is something he got wrong too, and it’s part of the reason the metaverse of Snow Crash feels very dated today: goggles. In Snow Crash, people don a headset to enter the metaverse; same in Ready Player One by Ernest Cline (2011), though he added haptic gloves. Stephenson now says: “It seemed like a logical assumption at the time that that would be the the output device. But that's not what happened. What happened is that everyone is accessing these 3D worlds through through two-dimensional flat rectangles on flat screens. And that works really well.” Indeed, one reason expensive VR headsets still haven’t gone fully mainstream is because you don’t need them to access virtual worlds. It works well enough for most people to do it on your computer. (Apple nonetheless has its own long-anticipated headset coming very soon; it’s hard to see how it will be a big hit, but on the other hand, it’s Apple.)

In fairness to Stephenson (and Philip K. Dick, William Gibson, Ray Bradbury, Aldous Huxley, Ursula LeGuin, and to an extent JG Ballard and Doug Coupland), the main reason seminal sci-fi novels like Snow Crash feel dated now is because they got so much right that what was then prescient now looks familiar.

The biggest impression rereading Snow Crash left on me was the reminder that I simply don’t want to spend time in the metaverse—any metaverse.

The metaverse, in almost all representations in fiction, is dystopian and unappealing. It is where dark, evil things happen. That’s not Stephenson’s fault, but it makes reading fiction about the metaverse somewhat unappealing. (One exception from a very recent release: the very clever “Pioneers” chapter of Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow—that game was a metaverse, in my view, though the word “metaverse” never appears in the novel.)

Decades of depictions of the virtual world in books and film (have you seen “Don’t Worry Darling” yet?) have firmly established: the metaverse is bad. Even when it’s good, it’s bad, because it becomes a drug: in the very underrated Shovel Ready by Adam Sternbergh (2014), the virtual world is so appealing as an escape from the apocalyptic real world that the rich plug into beds, nourished through IV drips, so that they can spend weeks in a row there. (Shades of Infinite Jest.)

The big tech companies now pitching a sunny version of the metaverse, in which you hold staff meetings or see a friend in a virtual bar for a virtual beer, are pursuing a dead end and should rebrand away from the metaverse entirely. Even for fun/social activities, it’s not very appealing.

As Stephenson said, “If you want lots of people going into the metaverse and having experiences, you've gotta create experiences that they enjoy having. It seems like a stupidly obvious thing to say, but there you have it. If it's purely a social space / cocktail party / endless people talking to each other kind of thing, then you can get some traffic with that kind of experience, but sooner or later people want to do something besides just talk to each other.”

But I digress. (How many readers have I already lost by this extended tangent on the mechanics of the metaverse? Oh well, back to books now.) Re-reading Snow Crash made me realize a nuance in my own sci-fi preferences: I prefer sci-fi set in space or other planets (Dune; Ender’s Game; Three-Body Problem; The Left Hand of Darkness; The Disposessed; Sea of Tranquility) to sci-fi set in a virtual computer world.

The other sci-fi sub-category I like: set on our world, but slightly altered (“through a mirror darkly”) in a recognizable near-future or dystopian future (Fahrenheit 451; Never Let Me Go; The Road; Station Eleven; American War; Wool; I Am Legend). I suppose those are all dystopian novels. Snow Crash and Neuromancer could also be called dystopias, but the difference is the examples I’ve listed are all set in the physical world, not a digital realm.

I think I prefer to inhabit the physical world, even when reading fiction. Maybe that’s surprising coming from someone who spends his working life on the internet.

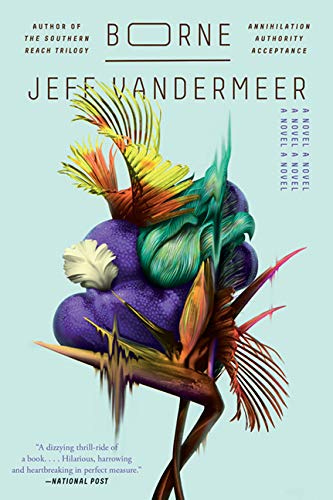

That brings me at last to another genre I’ve only recently gotten more into: eco sci-fi. I read Jeff Vandermeer’s Southern Reach trilogy (Annihilation, Authority, Acceptance) back in 2015 after the books first came out and I was floored. (Pro tip: skip the movie.) It was our world, but with changes to the natural environment that are scary and plausible—perhaps caused by our own actions, perhaps not. (I mentioned Annihilation in this 2021 issue as an example of a novel that gives me the same tingly feeling I get from Three-Body Problem and “Contact.”)

Last month, I read one of Vandermeer’s newer books, Borne (2017) and couldn’t put it down. The world is Earth, but in a ravaged landscape where plants have covered much of what’s left of the planet we ruined, and the surviving people live in the shadow of the remains of The Company and its biotech creations. Borne himself is a plantlike being with strange natural abilities, and it’s unclear whether he’s a piece of biotech created by The Company or a natural creation of the world. T(There’s also a giant evil flying bear and his legion of smaller bear minions.)

Climate change, erosion, pollution, endangerment of animal species, are all phenomenons that are very real today and are also ripe for riveting near-future sci-fi if followed to their worst possible conclusions. Other eco-fiction or eco-fiction-adjacent novels I’ve liked: On Such a Full Sea by Chang-Rae Lee; A Children’s Bible by Lydia Millet; Oryx and Crake by Margaret Atwood; The Vorrh by B. Catling.

Dune, at its heart, is eco-fiction too. Frank Herbert, in a foreword to Heretics of Dune (book 5) called “When I was writing Dune,” wrote that among many other things Dune was meant to explore (Messiah myth; energy sourcing; politics and economics; and predictive powers): “it was to be an ecological novel.” Over the course of the Dune series, Arrakis is at different points: dry and sand covered, green and verdant, dry and sand-covered again, and ultimately destroyed.

Could that happen to Earth?

Thanks for reading. If you enjoyed, please forward to your literary friends so that they subscribe too, or share on social. See you next issue. Hint: you’ll need your cowboy boots.