"Oh, my friend, my friend!"

When a novel about a dog turns out to be a novel about the act of writing fiction.

Good morning, welcome back, and thanks for reading Writing About Reading.

If you enjoy today’s newsletter, please forward it to a friend, and hit the ❤️, which will help me reach more readers. If you want to comment, click the Comment button at the bottom of this email. And if you aren’t yet subscribed, do it:

Right now I’m reading Child of God by Cormac McCarthy (novel) and Daddy by Emma Cline (short stories). I want to know what you’re reading. I’m not just saying that. Chime in.

If you’re new here, the last edition was an examination of three political dystopia novels (from 2017, 2004, and 1962), and the one before that was a look at Hunter S. Thompson’s political reporting (from 1972).

But now we’re through the election, and it’s time to turn off CNN and breathe out.

So let’s talk about dogs in fiction.

It strikes me as extremely difficult to write about dogs in any kind of unique way without it coming off as gimmicky.

You’re either doing anthropomorphic comedy (dog as human-like narrator) or trying too hard to get the reader to cry (beloved family dog gets lost, or goes on adventure; returns home; dies). Many of these stories have been made into tearjerker family films.

Paul Auster’s 1999 novel Timbuktu is narrated by a roaming dog named Mr. Bones (really) who befriends a homeless man named Willy Christmas. There are sentences like, “Thus began an exemplary friendship between man and boy.” A little girl begs her mother, “We’ve just got to keep him, Mama. I’ll get down on my knees and pray to Jesus for the rest of the day if it’ll make Daddy say yes.” Yes, Auster was parodying Norman Rockwell’s America, but Timbuktu still came off to me as cutesy and turned me off of his books for a while. (I love and recommend Invisible, The Brooklyn Follies, and The Music of Chance.)

The Art of Racing in the Rain by Garth Stein (2008) is narrated by an aging dog, Enzo, who adores his owner Denny, a race car driver. It’s wonderfully written, and Enzo’s narration isn’t corny, but his voice sounds more like a learned old man than a dog. The point of the book is to cry: Enzo is preparing for his own death (he believes he will be reincarnated), and Denny’s wife Eve gets brain cancer (Enzo knows it before the humans do, because he can smell it). You spend the whole book crying.

Speaking of reincarnation, one book that makes a dog narrator work is Mo Yan’s Life And Death Are Wearing Me Out (2006), which is long and challenging but extremely funny and rewarding. It’s about a Chinese farmer in the 1950s who is executed by his local government, then reincarnated (in his own village) as a donkey, still with his own brain and memories. He cycles through multiple lives in the book: donkey; ox; pig; dog; monkey; and finally, on New Year’s Eve in 2000, a human baby, the reward for all his trials. So the dog section is just one part, but it works because he’s speaking as himself, a man, in a dog’s body.

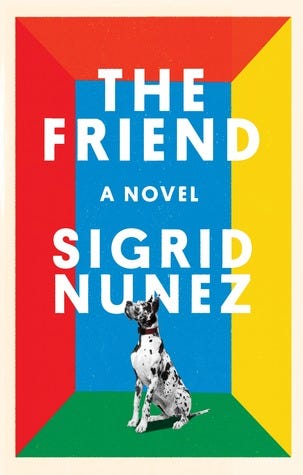

The dog is not the narrator of Sigrid Nunez’s 2018 novel The Friend, but in a way, he is the protagonist. The narrator is a teacher and writer whose close friend, also a teacher and writer, has killed himself. (Or has he?) She inherits his dog, a massive Great Dane named Apollo. (Or does she?) The structure of the book is very loose, with the speaker ruminating on love, teaching, and publishing, and her thoughts are addressed to her dead friend. But really the book is about Apollo and her relationship with him. It says something that only the dog gets a name; the narrator and her dead friend remain unnamed, and his three ex-wives are referred to as Wife One, Wife Two, etc.

It’s Wife Three who asks the narrator to take her friend’s dog. At first she declines, because her building doesn’t allow dogs and her apartment is tiny, and Apollo is so damn big. “There must be plenty of people who’d want a beautiful purebred dog,” the narrator says. Wife Three retorts, “Maybe if he was a puppy.”

She takes Apollo. He’s old and arthritic and huge, but extremely well-trained (though he does chew through a thick paperback Knausgaard volume when she leaves him in the apartment for too long one day). His presence calms her, and in turn has a calming effect on the reader. I love her musings about him: “I keep having fantasies like episodes from Lassie or Rin Tin Tin. Apollo foils burglars during attempted break-in. Apollo braves flames to rescue trapped tenants. Apollo saves super’s little girl from would-be molester.” Meanwhile her building super, Hector, keeps telling her she can’t keep the dog—he’s kind, but could lose his job if the landlord finds out.

She often reports her observations about Apollo in a straight, factual way that belies her rapidly-deepening love for him. “I can’t tell for sure whether Apollo likes to be massaged or is just tolerating it,” she reflects. “But I keep it up, getting him to lie first on one side then on the other, pausing for a chest rub in between. The chest rub is what he seems to like best. He doesn’t like having his paws touched, though the brat in me keeps trying… Apart, he is always on my mind and I am anxious to get back to him. He greets me at the door (has he been by the door the whole time?), but with a drowning look that says it hasn’t been easy, the waiting.” (Oh my god, that’s good.)

The dog’s closely chronicled tics lend a lightness to what is basically a grief memoir.

Another dog reflection I enjoyed: “Sometimes I find myself wondering, absurdly, what his ‘real’ name is. In fact, he might have had several names in his life. And what, after all, is in a dog’s name?” (This made me think of the reincarnation in Life And Death Are Wearing Me Out, and also of our dog Mumford, who was originally named Snoopy when my wife adopted him from a shelter in L.A.)

Of course, she talks to the dog out loud, like we all do: “Mostly I seem to ask questions. What’s up, pup? Did you have a nice nap? Were you chasing something in your sleep? Do you want to go out? Are you hungry? Are you happy? Does your arthritis hurt? Why won’t you play with other dogs? Are you an angel? Do you want me to read to you? Do you want me to sing? Who loves you? Do you love me? Will you love me forever?”

Note the ascending weight of those questions, from mundane to existential.

I don’t know if Sigrid Nunez has a Great Dane of her own, or any dog, and I don’t really want to know, but what I think would be hard about writing about a real-life dog is translating your extremely personal, private love to the page and conveying it to readers (strangers) without being sappy and solipsistic. You’re too close to it. I believe my dog is the most special dog there has ever been, and I believe no one has ever had a bond with their dog like I have with mine—but every dog owner believes that.

The narrator in The Friend makes frequent references to My Dog Tulip, a 1956 memoir by JR Ackerley about the romantic (but not sexual) relationship of the (gay, male) author and his (female) German Shepherd. I don’t typically like when novels spend a lot of time referring to a different novel (Michel Houellebecq’s Submission does this with the 1954 French erotic novel Story of O) but in The Friend I didn’t mind it because Nunez’s narrator knows she and Apollo represent an inversion of Ackerley and Tulip.

One could argue that the book is equally about writing as it is about the dog. Indeed, my copy is liberally underlined because there are so many trenchant asides about writing and the publishing world.

The narrator has serious hangups about what she does for a living: “Whenever he saw his books in a store, he felt like he’d gotten away with something, said John Updike. Who also expressed the opinion that a nice person wouldn’t become a writer. The problem of self-doubt. The problem of shame. The problem of self-loathing… If someone asks me what I teach, one of my colleagues says, why is it that I can never say ‘writing’ without feeling embarrassed.”

At the memorial for her friend, the narrator overhears someone say, coldly, “Now he’s officially a dead white male.” She reflects: “Is it true that the literary world is mined with hatred, a battlefield rimmed with snipers where jealousies and rivalries are always being played out? asked the NPR interviewer of the distinguished author. Who allowed that it was. There’s a lot of envy and enmity, the author said. And he tried to explain: It’s like a sinking raft that too many people are trying to get onto. So any push you can deliver makes the raft a little higher for you.”

And this, on the perils of writing about Brooklyn: “You who had moved there decades before the boom were disheartened to see Brooklyn become a brand and wondered at the fact that your own neighborhood had become as hard to write about as it was to write about the sixties counterculture: no matter how earnest one set out to be, the ink of parody seeped through.” (Sounds like the challenge of writing about dogs!)

With 20 pages left, Nunez turns the entire book on its head. The twist puts a spotlight on one of the biggest questions that writers agonize over: What and whom, from your real life, is it acceptable to write about in fiction?

The Friend is a slim book (200 pages), but it has stuck with me. I whipped through it in a few days after buying it from a store when it was brand new (the cover caught my eye—again, covers matter!) and then I re-read it more recently. I love the title. Is “The Friend” the narrator’s friend, or the dog? And the final line of the book killed me: “Oh, my friend, my friend!”

--

Thanks for reading with me. Please pass along to a friend (haha) who might enjoy it.