Travels with Vollmann

What an ace people-watcher can make from an old tootsie roll in a prostitute's pocket.

Good morning to all of you reading Writing About Reading. I’m toasting you with a hot mug of drip from my Mr. Coffee.

If you enjoy the newsletter today, please pass it along to your literary friends. If you want to comment, you can do that by clicking the Comment button at the bottom of this email. If you’ve read this week’s book, or if you read last week’s book, or have anything to say at all about your reading, post a comment. I want to hear from you!

I’m currently reading: The Souls of Yellow Folk by Wesley Yang and Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha by Roddy Doyle.

In case you missed it: last week’s edition was about The Sport of Kings.

And now: Issue 2 of the newsletter.

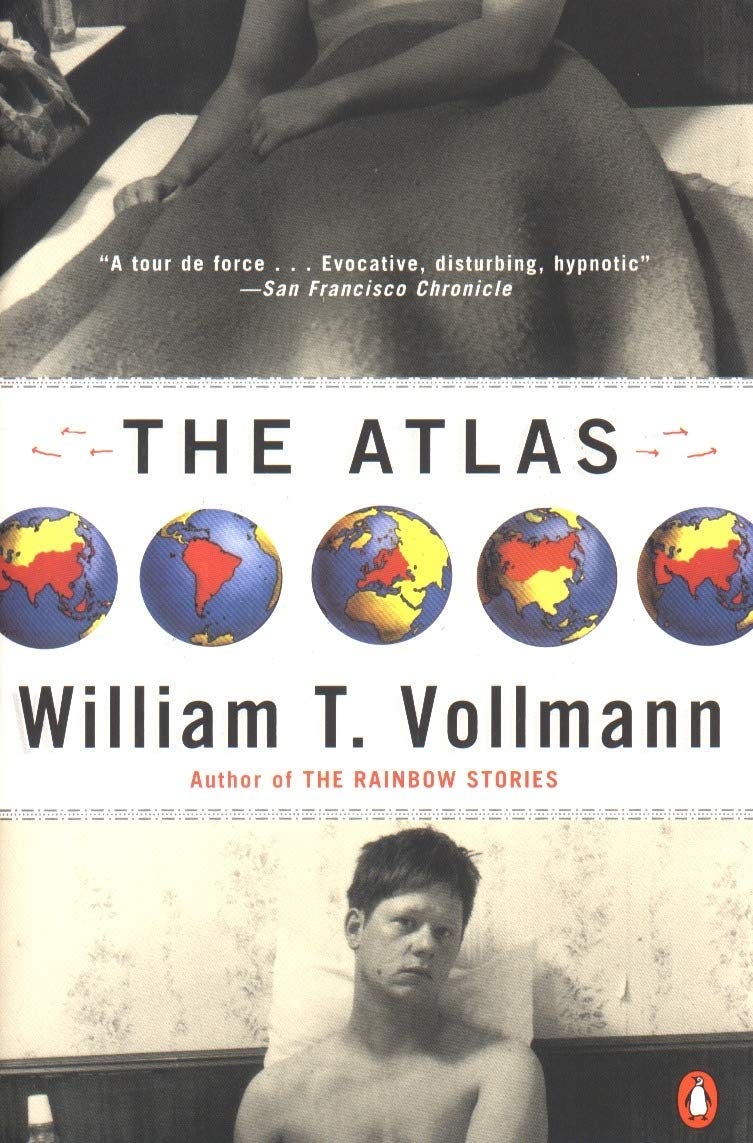

I have never agreed with the phrase, “You can’t judge a book by its cover.”

I’ve judged many books by their covers. The cover design is crucial for catching your eye in a store or even when shopping online. A great cover doesn’t mean the book will be great, but it’s a start.

The cover of The Atlas, William T. Vollman’s 1996 collection of travel stories, caught my eye in Waterstone’s in Dublin in 2008, when I was a traveler myself, living there and studying at Trinity. It remains one of my favorite book covers ever: the expression on the author’s face; the room he’s in, with the peeling wallpaper (some kind of hostel?); the design decision to flip the two halves of the photo, so his bottom half is at the top; the hand-drawn directional lines around the title. It all makes you look twice. (Many of his books have terrific covers, by the way. Check out the two below.)

I had never heard of Vollmann at the time. For someone so prolific (more than 26 books by age 60), who won the National Book Award in 2005 (for Europe Central), he remains arguably obscure to mainstream readers (the same is true of Will Self, one of my very favorites). His writing can be extremely dense and challenging; Alex Carnevale, founder of the blog This Recording, wrote in 2011 that Vollmann’s writing “is the product of ample research and a hefty dose of batshit crazy pills. No one writes books like William Vollmann, which is just as well, because part of what makes his historical intellectual romps so fascinating is that nothing like them has ever been attempted." (I tried and failed twice to read Poor People; his daunting 656-page debut novel You Bright and Risen Angels, about a war between insects and electricity, sits waiting on my shelf.)

He fascinates people. He has been everywhere, seen it all, done it all. As Madison Smartt Bell wrote in the Times in 1994, “Because he looks as if he has probably passed the last 10 years in a windowless room behind a computer terminal, you would be surprised to hear that he has spent the last few months swashbuckling through Thailand, Somalia and Bosnia with a disregard for personal danger that would shame Hunter S. Thompson, or Jack London, or Errol Flynn.”

The Atlas is the perfect entry to his body of work. I have returned to the book many times since first reading it in 2008; I just pick it up and flip to a random story.

Vollmann confirms that’s how his book can be read. He writes in his foreword that The Atlas was inspired by Palm-of-the-Hand Stories, a posthumously published collection of 70 very-short stories by the Japanese writer Yasunari Kawabata, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1968, “which I enjoy rereading at bedtime, in the five minutes between lying down and turning off the light… If you were to keep [The Atlas] by you as a pillow-book, reading through it in no particular order, skipping the tales you find tedious, dozing amidst my somniferous paragraphs, I’d feel that at last I’d done as much good in the world as the manufacturers of our drowsiest codeine syrups.”

Amid the pandemic, no one is doing any global travel. Everyone has a story of a trip they had scheduled for 2020 that they had to cancel. (Our big one was Running of the Bulls in Spain in July.) In lieu of real travel, let William Vollmann bring you to Thailand, Cambodia, Madagascar, Kenya, Mexico, Canada, and many other locales.

The book is arranged ingeniously by “stories” (more like chapters) containing scenes from multiple places, often as far apart as California and Somalia in the same chapter, loosely linked by the title of the story. Vollmann travels all over the world in the book, but California, Cambodia, and Thailand appear the most, and he’s most fascinated by drug addicts, poor people, young love, and prostitutes. (Janet Maslin wrote mockingly in the Times in 2007, “The trouble with Mr. Vollmann’s interest in whores is that it is apt to uncover hearts of gold.” I don’t have a problem with it.)

The collection opens in Grand Central Station in Manhattan. Here’s the first sentence. If you like this, you’ll like his writing, though it obviously requires slow, close reading: “Scissoring legs and shadows scudding like clouds across the marble proved destiny in action, for the people who rushed through this concourse came from the rim of everywhere to be ejaculated everywhere, redistributing themselves without reference to each other.”

That nails Grand Central, right?

Suddenly, two pages later, we’re in Sarajevo. (Vollmann covered the Bosnian War for Spin; in 1994, he and two other journalists, Brian Brinton and Francis Tomasic, ran over a land mine in their Jeep; Vollmann was injured, but the other two died.) One of the shortest and most memorable stories, “Are You All Right?” consists only of a quick phone conversation between Vollmann and a woman he met in Sarajevo. “Are you all right?” she asks him, and Vollmann says coolly, “A little shrapnel in my hand, but I wasn’t hurt.” (This is 1992, two years before the Jeep accident.) He tells her he’s leaving Sarajevo, and tells the reader that he can’t remember how the call ended: “My guilt about being free to leave has built a silence over time that drowned whatever she actually said. Every day I’d have liked to call her and ask: Are you still alive? Are you all right? But of course no one could call Sarajevo.”

The book carries you around the world, as Vollmann zooms in on people he observes or meets. Sometimes he’s describing scenes he witnessed from afar, removed; other times he’s part of the scene. He smokes crack with prostitutes in San Francisco, swims with Inuit teens in the Northwest Territories of Canada. Vollmann is a character in his own reporting, like the journalism of Hunter S. Thompson, Tom Wolfe, Joan Didion, and Jon Krakauer.

Throughout my copy, I’ve underlined passages that astonished me.

In Sarajevo, Vollmann watches a “man with a military crewcut who sat smoking: his hair was the color of his smoke.”

In Nebraska, he writes, “Past the heat-seared road weeds, past the Tomahawk truck stop, I found the magic barrier crossing which once had filled me with awe and exaltation so many years ago when I left the east forever (so I’d thought) by Greyhound; now it eased me, pleased me, but could not help me anymore.” We all have memories of bus trips like that.

The book also features a series of photographs taken by Vollmann; they are mostly portraits of people, and they are un-captioned, which gives them a universality.

In San Francisco, Vollmann gives a prostitute a twenty to go buy crack, and makes her leave her jacket behind to make sure she’ll return. When she doesn’t return, he takes inventory of the jacket pockets: “I found three lighters, a tube of vaseline, lots of dirty tissues, a hamburger wrapper wet and yellow with oil, a broken cigarette, some matches, and finally, like some sweet secret, a little Tootsie Roll. Something about the Tootsie Roll touched me, I don’t know why. It was like her, the dearness of her hidden inside all the greed and the lies… I left the coat in the hallway where she could get it if she ever came back. I wanted to keep the Tootsie Roll but that would have been like robbing her of her soul. In the end, just so I wouldn’t feel like a complete chump, I stole one of her cigarette lighters… Later, I took the lighter out in order to strike an idle flame, but then I saw that it had no flint. I wondered what would have been wrong with the Tootsie Roll.” Holy shit.

He can also be extremely funny, usually deadpan, like this moment early in the book: “When I was standing outside one of the apartment buildings near the front, waiting for my friend Sami to buy vodka, I felt a sharp impact on the crown of my head. Reaching up to explore the wound, I felt wetness. I took a deep breath. I brought my hand down in front of my eyes, preparing myself to see blood. But the liquid was transparent. Eventually I realized that the projectile was merely a peach pit dropped from a fifteenth-floor window.”

In Australia in 1994, Vollmann and his wife exit a taxi, and as his wife stands on the sidewalk waiting, the driver whispers to Vollmann, “You’ve put some miles on her. Better trade her in for a new one as soon as you can. You want me to tell you where to go in Sydney?” Vollmann writes: “Looking into his eyes, I saw such raw wet pain in them, throbbing and obscene, that for a moment I could not breathe.”

I admire that Vollmann has committed his career to trying to understand people who are not like himself.

Before a 2005 reading at SUNY Albany (you can watch it here), Vollmann said, “I’ve always thought that one of the things that a writer should try to do is empathize with the ‘other,’ whatever the ‘other’ is. That doesn’t mean that you have to like or admire the ‘other,’ but if we’re going to judge other people in the world, if we want to decide who’s on the side of the angels, for instance, George Bush or Al-Qaeda, it would be nice to get into both of their heads.”

He has tried to reckon with his privilege as a journalist, someone who can parachute in to the lives of others to hear their stories, but can exit whenever they feel like it.

At one point in The Atlas, he asks himself, in a moment reminiscent of Chekhov’s famous ‘man with a hammer’: “Which is worse, to be too often protected, and thereby forget the sufferings of others, or to suffer them oneself? There is, perhaps, a middle course: to be out in the world enough to be toughened, but to have a shelter sufficient to stave off callousness and wretchedness.”

--

Thanks for reading with me today. If you enjoyed, please forward to a friend.

Coming up next week: Weird baseball fiction.