The unfinished

Marquez's "Until August," DFW's "Pale King," and what to do with unfinished novels by the greats

Good morning and welcome back to Writing About Reading.

In the two months since last issue, I’ve read: Devil’s Bargain by Joshua Green (about Steve Bannon’s pivotal role in getting Trump elected the first time—fascinating read for right now, with history repeating itself with Trump as candidate for the third consecutive cycle); Wellness by Nathan Hill (satirizes and nails so much of contemporary life in suburban America for married couples with children, highly recommend); The Golem of Brooklyn by Adam Mansbach (a recommendation from a W.A.R. reader and friend, quick-and-funny read for Jewish humor lovers that loses steam toward the end); Knife by Salman Rushdie (one of my heroes, this is his devastating but necessary account of the attack on his life in August 2022 at the Chautauqua Institution in New York in which he lost an eye—it is by no means where you should start if you’ve never read Rushdie, start with Satanic Verses or Midnight’s Children, or Fury or Shame for something shorter, or his first memoir Joseph Anton); North Woods by Daniel Mason (this sprawling, brilliant, “impossible-to-summarize” novel told in multiple formats by multiple narrators spans 300 years in the life of one Massachusetts house, and is stuffed with ghosts, seances, insects, catamounts, and so much more); Down the Great Unknown by Edward Dolnick (an account of one-armed geologist John Wesley Powell’s brazen 1869 expedition down the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon—recommend for lovers of Jon Krakauer and outdoor adventure/disaster nonfiction); and Until August, the just-released posthumous novella by Gabriel Garcia Marquez, the book I want to ruminate on today along with another posthumous novel I know intimately.

What have you all been reading?

As a guiding question for today’s issue: Is it right to publish an author’s unfinished work after they’re dead without their explicit permission? How about in direct opposition to their stated wishes?

That appears to be the case with Until August, published in March on what would have been the author’s 97th birthday (he died in 2014).

I should say as background that the only Marquez I had read was One Hundred Years of Solitude, back in high school, and I remember only that the writing was beautiful, that it was an Important Novel, and that Marquez is associated with magical realism. Until August is not magical realism. (In this way, starting with Until August as your entry to Marquez’s body of work would be like how my first Murakami was Norwegian Wood.)

The review of Until August in the latest NY Review of Books (one of my cherished print subscriptions) written by the playwright Ariel Dorfman (a personal friend of Marquez), captured my interest with the publishing backstory: Toward the end of his life, Marquez suffered from dementia. After his death, the manuscript of Until August ended up in the Ransom Center archives at the University of Texas Austin, until his sons Rodrigo and Gonzalo took it back and published it—this even after Marquez’s final comment on the matter was: “This book doesn’t work. It must be destroyed.”

They did the opposite of destroying it. Here’s their defense, explained in a brief preface to the English edition: “Judging the book to be much better than we remembered it, another possibility occurred to us: that the fading faculties that kept him from finishing the book also kept him from realizing how good it was. In an act of betrayal, we decided to put his readers’ pleasure ahead of all other considerations. If they are delighted, it’s possible Gabo might forgive us. In that we trust.”

As Dorfman writes, the publication of Until August “has stirred a considerable amount of controversy, with many arguing that it is a disservice to allow such an unfinished minor work to circulate.”

Until August is a short work (144 pgs, including notes), but it doesn’t feel “minor.” The story is tightly told and carries you along gracefully as it escalates. Ana Magdalena Bach, a 46-year-old woman, happily married, takes a solo trip to visit her mother’s grave on an island off the coast of Colombia every August on the anniversary of her mother’s death. On the visit that opens the novel, she does something rash: she has a one-night-stand with a stranger she meets in the hotel bar, “a step that had never occurred to her in her entire life, not even in dreams, and she took it without any mystique: ‘Shall we go up?’” She’s the pursuer, she’s the driver of the action, and she greatly enjoys herself that night.

In the years that follow, she attempts to have a one-night stand on every trip, always with a different stranger, not always with happy results. And the first man had left a twenty-dollar bill for her after the encounter (tucked into the book she was reading, Bram Stoker’s Dracula), which enrages and haunts her for the rest of the novel. She returns home from that first dalliance feeling that things at home have changed, until she realizes “the changes were not to the world but to herself… She did not know why she’d changed, but it had something to do with the twenty-dollar bill she carried around at page 116 of her book. She had suffered unbearable humiliation, without a moment’s serenity. She had wept with rage from the frustration of not knowing the identity of the man she would have to kill for debasing the memory of a happy adventure.”

The writing is wonderful and understated. (One quick example: “After the second drink she felt that the brandy had met up with the gin in some corner of her heart.”) And when the climactic moment of the book arrives, it is relayed as suddenly and nonchalantly as the first moment she cheats on her husband: “She got up determined to take the plunge she hadn’t known how to take during her bad island nights.” What plunge? An act that no reader will expect. I’ll stop just short of sharing what she does next, for anyone who plans to read the book. I recommend you do.

Okay, so I’ve summarized the controversy here, and I’ve relayed that the book is wonderful—even if it was unfinished, in Marquez’s eyes. What I haven’t done is answer my own question of whether it was right for the sons to publish this book, against the stated wishes of their father.

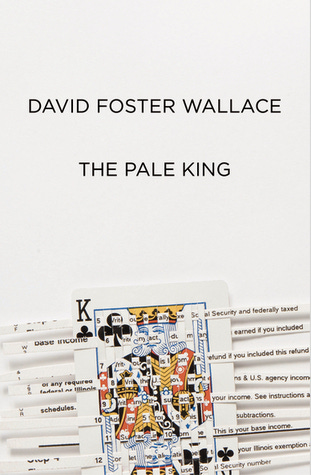

First, let me invoke a very different posthumous novel: The Pale King by David Foster Wallace.

I am something of a DFW nut, though nowadays that is considered extremely uncool, even embarrassing. I wrote my college senior thesis on the journalism tricks of Wallace and Hunter S. Thompson, I’ve been on the Wallace list-serv for over a decade, and I’ve written about Wallace for Salon, NPR, Berfrois, and other places. I am not an Infinite Jest fanboy (read it, didn’t love it); I’m far more interested in his non-fiction essays (though his short story collections are also outstanding). It feels to me a hallmark of this American cultural era that one of the most gifted writers of his generation has been half-canceled after his death when he is no longer here to defend himself, but I’ll leave that thread alone for this issue and focus on this one book.

Wallace died by suicide in 2008, and The Pale King, his third novel, was published in 2011. I reviewed the novel for NPR.org when it came out. The backstory goes like this: after his death, Wallace’s widow Karen Green and his agent Bodie Nadell found the novel in fragments across hard drives, paper notebooks, and files on his computer. He had attempted to organize the fragments into apparent chapters before his death, suggesting his intention that it be published, but he left no explicit directions. Wallace’s editor Michael Pietsch at Little, Brown, did the grunt work of culling more than 1,000 pages down to 538. Even at 538 pages, the story is unresolved, and might have been twice as long if Wallace had had his way. As John Jeremiah Sullivan wrote in GQ in 2011, “He left us this book—the people closest to him agree that he wanted us to see it. This is not, in other words, a classic case of Posthumous Great Novel, where scholars have gone into an estate and unearthed a manuscript the author would probably never want read. Wallace seems to have laid this book before us in an all but do-with-it-what-you-will sort of way… Think of a big mural that was half done.”

I loved The Pale King and (hot take!) think it’s a more enjoyable read than Infinite Jest (1,079 pages). It has stretches of occasional intentional boredom, as it’s set at an IRS office in Peoria, Illinois, but it also has hilarious characters and stretches of brilliance unmatched in any other Wallace fiction. One long section, the first-person backstory of a character named Chris Fogel, was published as a standalone novella by McNally Jackson in 2022 (a la “Pafko at the Wall” from DeLillo’s Underworld) that they titled Something To Do With Paying Attention. That section boasts one of the most incredible scenes Wallace ever wrote:

I was by myself, wearing nylon warm-up pants and a black Pink Floyd tee shirt, trying to spin a soccer ball on my finger and watching the CBS soap opera “As The World Turns” on the room’s little black-and-white Zenith… at the end of every commercial break, the show’s trademark shot of planet earth as seen from space, turning, would appear, and the CBS daytime network announcer’s voice would say, “You’re watching ‘As the World Turns,’ ” which he seemed, on this particular day, to say more and more pointedly each time—“You’re watching ‘As the World Turns’ ” until the tone began to seem almost incredulous—“You’re watching ‘As the World Turns’ ”—until I was suddenly struck by the bare reality of the statement… It was as if the CBS announcer were speaking directly to me, shaking my shoulder or leg as though trying to arouse someone from sleep—“You’re watching ‘As the World Turns.’” I didn’t stand for anything.

Anyway, I don’t want this issue to become a paean to The Pale King. I mention it in contrast to the circumstance around the publishing of Until August. David Foster Wallace, presumably, would not be angry that The Pale King was published, though perhaps he’d quibble with many of Michael Pietsch’s editing decisions. He took actions to indicate that he wanted it to see the light of day. Gabriel Garcia Marquez told his family not to publish Until August, in fact he said it must be “destroyed.” (Again, he was also suffering from dementia.) They directly disobeyed him.

But in the end I feel that wonderful writing deserves to be read. I think Marquez’s sons framed it perfectly, and lovingly, in their preface: if the book delights readers, they reasoned, perhaps their father would forgive them.

I was delighted by it, and I believe he would.

If/when a great author leaves behind an unfinished work that still possesses some of their greatness, you take it, do your best to package it, and give it to their readers.

That’s all for today. Thanks for reading. Keep reading.