High

Jeet Thayil's novel of a grieving husband on a drugged-out trip in Bombay is lyrical and often hilarious.

Good morning!

Right now I’m reading Dead Astronauts by Jeff Vandermeer (sequel to Borne, which I mentioned loving in Issue 16) and Inland by Téa Obreht. Waiting patiently on my beside to-read table are Trust by Hernan Diaz and Here I Am by Jonathan Safran Foer. What are you reading? I’m interested, I mean it, and you can use the public comment feature or reply to this email to tell me.

If you enjoy these emails, please forward to your friends. If a friend forwarded you this email, please subscribe:

All of my past few issues started by focusing on one book and ended up being a much broader survey, either of an entire series (Cormac McCarthy’s Border Trilogy; Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall series; Frank Herbert’s Dune sequels) or a sub-genre of fiction (metaverse sci-fi; alien sci-fi). I’d like to get back to doing a breezy issue about a single novel I loved. The last time I did this was with Normal People in March 2021; also see my issues on The Apartment and The Friend.

In that spirit, let’s get high.

Just like it’s very challenging (or so “they” say) for actors to plausibly play drunk or high, I believe it’s not easy to write well about characters who are drunk or high. But Jeet Thayil represents an extreme form of “write what you know”: he is a recovered heroin addict whose wife died suddenly in 2007 at age 27.

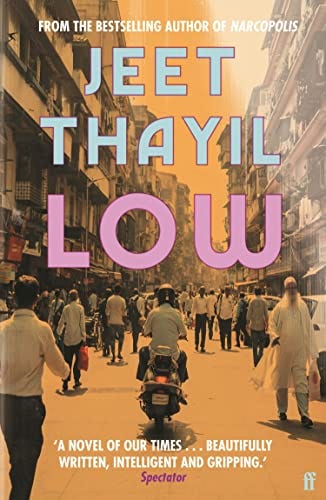

Those experiences directly informed his first novel Narcopolis (2012), which was shortlisted for the Booker Prize, and Low (2020), which in my view was criminally overlooked by the literary establishment. (Could timing have been a cause? Publishing a novel in 2020 proved unlucky for many.)

The two novels have the same narrator, Dominic Ullis, though in Narcopolis you don’t learn his name until 19 pages before the end, when the still-unnamed narrator returns to Bombay years after the action of the book and someone recognizes him: “You’re Dom Ullis. We used to call you Doom or Dum… sometimes I called you Damned Ullis because of the things you said.”

Narcopolis followed a panoply of drug addicts who frequent an opium den in Mumbai in the 1970s. Though Ullis is the all-seeing narrator, the story drops in on all the many characters in turn. Where Narcopolis is sweeping, Low is zoomed-in, focused wholly on Ullis. Narcopolis spans a period of years, Low takes place over a single weekend. Narcopolis is about poor people smoking opium, Low is about rich people doing cocaine, heroin, and meow meow (mephedrone). Thayil told Vice, “In Narcopolis the drugs are our vehicle from which to look at a certain era that has absolutely vanished. In Low, drugs are the vehicle to look at grief.”

It’s decades after Narcopolis and Ullis has come back to Bombay to spread the ashes of his wife, who killed herself in Delhi with little warning. After the cremation, Ullis gets in a cab and heads to the airport on a whim rather than going home to the empty apartment he shared with his wife. He has nothing with him but a box of her ashes.

That may sound like a grim setup, but the brilliance of Low is how much humor Thayil wrings from a tragic character in a tragic moment of his life. I repeatedly laughed out loud—an impressive feat to wring humor out of a grief plot.

It’s funny from the very beginning, when a rich older woman next to him on the flight to Bombay steals the airline silverware and headphones, and gets up too soon when the plane has barely touched down and gets scolded. She asks his name, he says “Ullis,” and she mishears and calls him “Ulysses” for the rest of the book.

Later on, in one of many howling passages, the woman (Payal) is left alone with Ullis’s bag (containing Ullis’s dead wife’s ashes) and she does this:

After he toddled off on his chore, she’d felt compelled to open the backpack and take a look inside. The white box had intrigued her - imagine, a backpack that held nothing more than a mid-sized box of powder - and she’d been further compelled, even duty-bound, to try a cautious initial line. It wasn’t the best coke she’d ever had, and it certainly was not the worst, not by a long shot. She cut a few more lines, remarking at the lumpiness and strange colour. But she had enjoyed the effects, delicate and refined, as good as the best Colombian. Without a doubt it was designer stuff.

When Payal introduces him to some of her friends, she says, “Meet my dear friend Ulysses, who has come a long way to join us tonight,” and does it “with a flourish of the hands, as if she were presenting a Homeric hero rather than a shoeless grief-struck stranger half out of his mind on Chinese heroin and the ashes of his own dead wife.”

Much of the humor comes from the characters Ullis encounters as he, the straight (but drugged) man, coasts along. Text messages from Danny, his local drug dealer, are especially funny: “Got me this time excellent stone white stuff on rock form untouch plus cooked one crack n lsd crystal mdma n h-in.” Ullis wonders in response to that one: “Did Danny really think it was okay to list crack, LSD, crystal meth, and MDMA in a text, but heroin alone required a coy ‘h-in’? What was wrong with him?”

As Ullis floats on different drugs through various bizarre social encounters, we get memories of his marriage, and these are the sections where Thayil can kill you with one interjection, like when he’s remembering a conversation in which his wife called him Dommie, and he thinks, “Who would call him Dommie again?” Or when a cabbie driving him around assures him, “I am exceedingly safe driver” and Ullis reflects, “Of course he was right. Nothing bad could happen because the worst had occurred.”

He blames his own “fatal inaction” and his “abject failure as a husband and a man” for her suicide.

But the drugs help. After getting sick from too much drugs, he’s ready for more drugs: “The sight of the vomit made him feel better almost instantly. At least now he was ready for more heroin.”

In both novels, there’s a strong sense of apathy from the addicts, like once you’re an addict, there’s not much more to do but keep at it. From Narcopolis:

That was when Dimple asked the question I couldn’t answer for many years. She asked why it was that I, who could read and write and had a family that cared enough about me to finance my education, who could do anything I wanted, go anywhere and be anyone, why was I an addict? She didn’t understand it.

At the time, I couldn’t either. I didn’t know my own compulsions well enough to reply. Instead, I broke out the pharmaceutical morphine I’d stolen from the office stores and made myself a small shot.

And the addicts take their habit seriously. In Rashid’s opium den, “the room made people talk in whispers, as if they were in a place of worship, which, the way he saw it, they were.”

Thayil is an accomplished poet, and it shows in Narcopolis in particular, which opens with a seven-page sentence—but never fear, this is no dense Faulknerian or Proustian slog, it’s graceful, easy, and funny. Here’s just the first part:

Bombay, which obliterated its own history by changing its name and surgically altering its face, is the hero or heroin of this story and since I’m the one who’s telling it and you don’t know who I am, let me say that we’ll get to the who of it but not right now, because now there’s time enough not to hurry, to light the lamp and open the window to the moon and take a moment to dream of a great and broken city, because when the day starts its business I’ll have to stop, these are night-time tales that vanish in sunlight like vampire dust – wait now, light me up so we do this right, yes, hold me steady to the lamp, hold it, hold, good, a slow pull to start with, to draw the smoke low into the lungs, yes, oh my, and another for the nostrils, and a little something sweet for the mouth, and now we can begin at the beginning with the first time at Rashid’s when I stitched the blue smoke from pipe to blood to eye to I and out into the blue world – and now you’re getting to the who of it and I can tell you that I, the I you’re imagining at this moment, a thinking someone who’s writing these words, who’s arranging time in a logical chronological sequence, someone with an overall plan, an engineer-god in the machine, well, that isn’t the I who’s telling this story, that’s the I who’s being told, thinking of my first pipe at Rashid’s…”

But I digress. I come to praise Low, which you can read and enjoy without reading Narcopolis.

Back in 2011, the “it” novel of the moment was Open City by Teju Cole, a perambulation diary in which a man walks around New York City encountering various characters, and not much happens. That novel was breathlessly compared at the time to Sebald, and raved about by the important critics—but I found it painfully boring. Low feels to me like a similar type of novel, but one that actually succeeds for its wit and self-deprecation. Low doesn’t take itself too seriously, even though what’s happening to Ullis is plenty serious.

And because its protagonist exists in a state of almost constant high, it feels totally natural that at some point he begins talking to the ghost of his dead wife, pestering her to explain herself and her actions. (He sings “Stupid Girl” by Garbage to the backpack containing the ashes, in the hopes his wife will hear it.)

The same thing very briefly happens to Ullis in the final pages of Narcopolis when he finds the ghost of his dead friend Dimple sitting on the toilet in her old apartment, and she tells him, “I’m not a ghost. I’m still here. I’ve been here all this time but I kept out of your way. Dead do not always become ghosts. We are like dreams that travel from one person to the other. We return, but only if you love us.”

The title, by the way, comes from Ullis’s dead wife’s own name for the place she’d go, emotionally, when depressed: she would tell him, “I’m going to the low.” Ullis spends the novel both “in the low” and also extremely fucking high, and the combination makes for a bewitching concoction.